Diarmuid Lynch is buried in a quiet corner of Tracton Abbey Graveyard belying his central role in the drama of 1916 and the subsequent struggle for Independence.

Born in Tracton, in January 1878, his formative years were influenced by the bitter struggle of the Land War and the rejection of Parnell’s attempts to secure home rule for Ireland.

Indeed, he’s believed to have attended the public meeting in Cork city, were Parnell uttered the immortal words.

“No man has a right to fix the boundary to the march of a nation. No man has a right to say to his country thus far shalt thou go and no further.”

The statement is now em blazed on Parnell’s monument, on the square that bears his name in Dublin.

Having initially travelled to work in the Post Office in London, at Mount Pleasant, a venue that would ultimately become a hot bed of Irish nationalism, with the arrival of Michael Collins and Sam Maguire, Diarmuid left for America

It was in the Big Apple that Lynch learned his trade as an Irish Nationalist, having become a close associate to Judge Coholan, and John Devoy as well as the unrepentant Fenian, O’ Donovan Rossa.

He would later return to Ireland and immerse himself in the fledgling Sinn Fein Party, founded by Arthur Griffith, who promoted the idea of a Dual Monarchy as a way to appease the Ulster Protestants in joining a sovereign government in Dublin.

It was during this period that he established several important personal relationships, including Sean MacDiarmada, particularly in the 1908 by-election in Leitrim, when both men escaped from an assault by members of the Irish Parliamentary Party.

As his involvement with the separatist movement grew, he began to find himself at the heart of the cause, sworn in the IRB by Sean T O’ Kelly.

O’Kelly as President of Ireland and attending Lynch’s funeral in 1950, would abandon the state car at Minane Bridge Church and walk with the funeral procession, as a mark of significant respect to Lynch’s contribution to Irish freedom.

Now a member of the Supreme Council of the IRB, Lynch was at the heart of planning the Rising, he was detailed by Padraig Pearse to identify the location of the expected arms shipment in Kerry.

Indeed, when McNeill’s counter orders to cancel the planned volunteer’s activities for Easter looked to have scuttled the attempts of a rising, it was Lynch at a specially convened meeting of the Military Council of the IRB that pushed through the necessity of the Rebellion to go ahead.

Easter week found Lynch in the GPO as an aide-de-camp to James Connolly, as the burning building was evacuated from the British shelling, Lynch was the last man to leave the GPO, with reports that his uniform was smouldering.

(His uniform is now in the public museum in Fitzgerald’s Park).

Initially, sentenced to death for his part in the Rising, like de Valera, American citizenship, saw his sentence commuted to a prison sentence.

Released under a general amnesty in 1917, he returned to Ireland, where he held three senior posts in the IRB, Sinn Féin and the Volunteers, with only Michael Collins also holding three senior similar posts.

Arrested and exiled to America for his activities, but not before he married his girlfriend in Dundalk prison, much to the British Authorities embarrassment.

In America, he was again back at the centra of activities, raising funds but at home he was elected to the first Dail as a TD for South Cork in December 1918.

With de Valera’s arrival in American, he travels with him across the States, but like many stateside, the Irish leader, doesn’t endear himself to Lynch or his American friends.

Like many of his comrades he stays out of the Civil War and made several attempts to broker a peace but to no success.

Following the Civil War, he stays in America and becomes an assistant to the ageing Devoy but he’s also engaged in a successful court battle with De Valera on the ownership of funds raised in America.

He returned to Ireland and was involved in the collection of witness statements for the Bureau of Military History, which now play such an important part of today’s research of the period.

Living out something of a quiet existence in Tracton, he passed away in November 1950 and is buried in Tracton Abbey Graveyard.

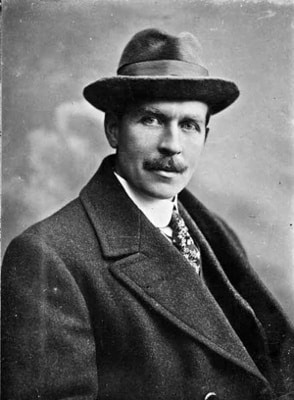

Diarmuid Lynch